Let’s be honest: GDPR isn’t the most thrilling part of your job. It’s not going to earn you a gold star or a round of applause in the staffroom. But it will keep your school safe, your students protected, and your inbox free from the dreaded “URGENT: Possible Data Breach” email.

So if you’re an educator juggling lesson plans, safeguarding concerns, and the occasional coffee spill, here’s your friendly reminder that data protection is a daily habit, not a once-a-year training module.

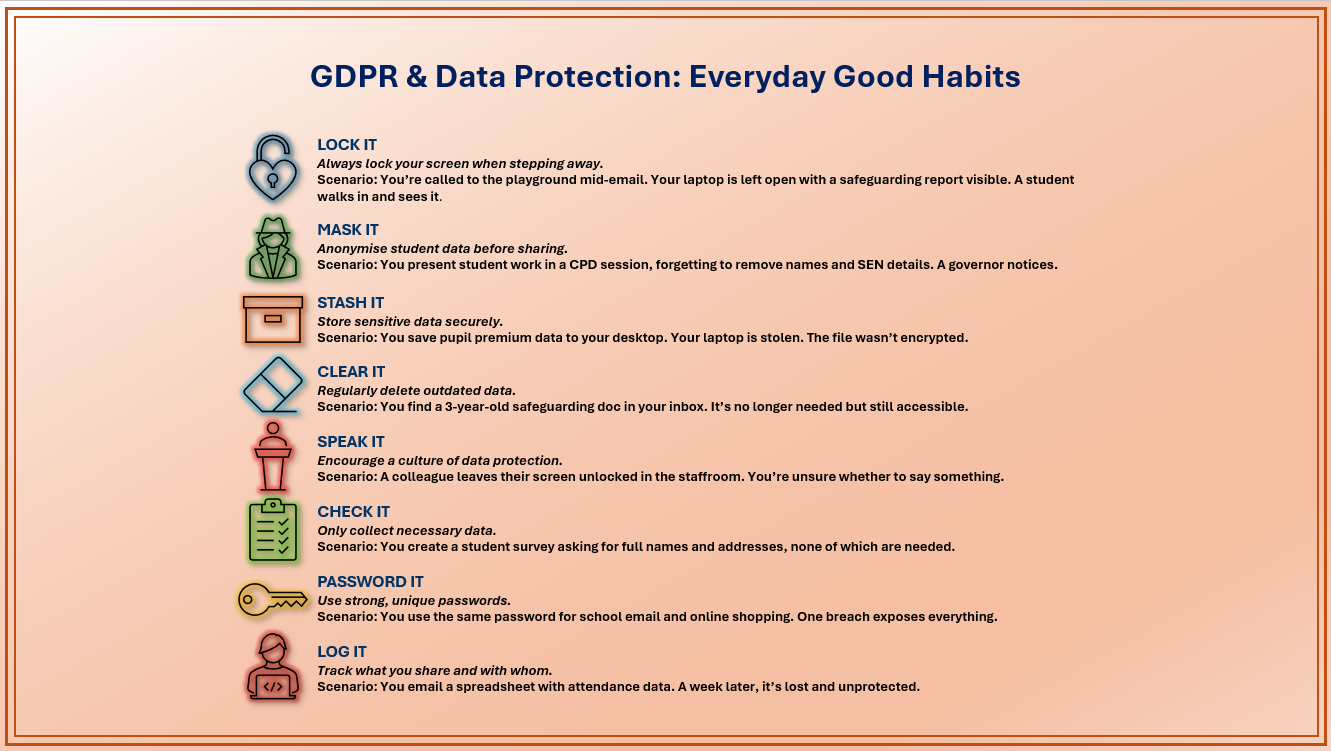

Let’s revisit our trusty trio – Lock it, Mask it, Stash it, and add a few more good habits.

Lock It – Because Screens Don’t Need an Audience

Scenario:

You’re called out of your classroom to deal with a playground incident. In your rush, you leave your laptop open on your desk with a safeguarding report on the screen. A curious student wanders in and sees more than they should. Later, they mention it to a friend, and suddenly sensitive information is circulating.

Good habit:

Hit Windows + L or Ctrl + Command + Q on a Mac every time you step away. Set your device to auto-lock after a few minutes. It’s like closing the door on sensitive data.

Mask It – Anonymise Like You’re in a Spy Movie

Scenario:

You’re leading a CPD session and want to showcase a brilliant piece of student work. You project it on the screen… and realise too late that it includes the student’s full name, class, and SEN status. A visiting governor notices and raises concerns.

Good habit:

Before sharing, ask: “Could someone identify this student?” If yes, anonymise. Use initials, remove photos, blur names. Think MI6, but with worksheets.

Stash It – Store Smart, Not Just Somewhere

Scenario:

You save a spreadsheet of pupil premium data to your desktop “just for now.” Weeks later, your laptop is stolen from your car. The file wasn’t encrypted. Cue panic, paperwork, and a very uncomfortable conversation with leadership.

Good habit:

Use school-approved cloud storage. Encrypt sensitive files. Never store personal data on USB sticks unless they’re encrypted and never leave them in your coat pocket.

Clear It – Declutter Your Digital Life

Scenario:

You search your inbox for a parent’s email and stumble across a safeguarding document from three years ago. You don’t need it anymore, but it’s still sitting there, vulnerable. If your account were compromised, that data could be exposed.

Good habit:

Schedule a monthly “data declutter.” Delete what’s outdated, archive what’s essential. GDPR loves a tidy inbox.

Speak It – Make Data Protection a Team Sport

Scenario:

You notice a colleague leaving their screen unlocked in the staffroom while they grab a coffee. You hesitate to say anything… but what if a student walks in? Or a visitor?

Good habit:

Speak up. Start a “Data Protection Minute” in staff meetings. Share one tip, once a month. It’s painless, and it builds a culture of care.

Check It – Know What You’re Collecting (and Why)

Scenario:

You create a Google Form to collect feedback from students. You ask for full names, dates of birth, and home addresses (none of which are actually needed). A parent complains after seeing the form.

Good habit:

Stick to data minimisation. Only collect what’s necessary. If you don’t need it, don’t ask for it. Less data = less risk.

Password It – Strong, Unique, and Not “Password123”

Scenario:

You use the same password for your school email, your personal Netflix account, and your online shopping. One breach, and everything’s exposed. Worse, your school account is used to send phishing emails to parents.

Good habit:

Use a password manager. Enable two-factor authentication. And never write your password on a sticky note stuck to your monitor (yes, we’ve all seen it).

Log It – Keep Track of What You Share

Scenario:

You email a spreadsheet to a colleague containing student attendance data. A week later, they can’t find it, and you’re unsure who else might have access. You didn’t password-protect it, and now it’s floating around inboxes.

Good habit:

Keep a simple log of what you’ve shared, with whom, and when. Use password protection for sensitive documents and send passwords separately.

You don’t need to be a tech wizard or a GDPR guru. You just need to be mindful, and act. Every locked screen, anonymised document, and securely stored file is a step toward a safer, smarter school.

So next time you’re tempted to save something “just for now” or leave your laptop unattended, remember: Lock it. Mask it. Stash it. Clear it. Speak it. Check it. Password it. Log it.

Your students deserve it. Your school depends on it. And your future self will thank you.